Mummies and the Usefulness of Death

What do ancient Egyptian mummies, early modern medicines, a 19th-century philosopher, and a 21st-century chemist have in common? Published in Chemical Heritage Magazine, Fall 2014

In Oakland, a center works to protect Cambodian girls from sexual exploitation

On a Friday night in December, ten girls between the ages of 11 and 20 gathered in a warmly lit, living room-esque space at Oakland’s Center for Empowering Refugees and Immigrants (CERI) on International Boulevard. They sprawled throughout the room on couches, chairs, and pillows, silently watching Very Young Girls, a 2007 documentary about girls in New York City who were coerced by pimps into working as prostitutes.

CERI is a non-profit organization that provides mental health and social services to refugee and immigrant families, mostly Cambodians. All of these girls’ parents are Cambodian refugees, and they all live in high crime neighborhoods in the East Bay. Many of them know other girls—friends, former classmates—who have become involved in “the life,” a term for the underground world of prostitution.

“The Cambodian youth in Oakland is at risk,” said Mona Afary, the executive and clinical director of CERI, who facilitates, among other programs, a support group for young girls. This particular group started its work in July, 2011, through a contract with the Alameda County Behavioral Healthcare Services with the funding from Proposition 63, the Mental Health Services Act.

Sgt. Holly Joshi of the Oakland Police Department’s vice and child exploitation unit said that her unit sees an average of 100 commercially sexually exploited minors each year. Underage girls make up ten to 20 percent of all prostitution arrests in Oakland, she said, but added that it’s hard to calculate the numbers of minors involved with sex trafficking because unless a girl or a pimp is caught, the crime goes unreported. With fewer officers and resources, the OPD has not had the capabilities of organizing stings to the extent they once did. Also, in this economic climate, Joshi pointed out, men might decide that pimping is more financially lucrative than selling drugs.

While it’s hard to find numbers regarding the ethnic breakdown for young girls who are being sexually exploited, Afary worries that this issue disproportionately affects Asian girls because some people perceive them to be “exotic.” She is also concerned that Cambodians in Oakland often live in high-crime, low-income areas where pimps are most likely prey on young girls.

At the CERI movie night, the on-screen images of streets in Brooklyn and the Bronx bore some resemblance to the streets just past the center’s doors—the center, and the homes of the girls in Afary’s support group, are located not too far from “the track,” a stretch of International Boulevard near 19th Avenue known for sex trafficking. The girls in the film were no older than the girls in the center’s living room. One girl watching the movie wiped a tear from her eye as one of the documentary’s characters described how she fell into the life after feeling like no one loved her. Others seemed to be watching in stunned silence.

After the movie had concluded, the girls at the meeting reflected on the film by painting and writing poetry. One of the poems began: “Little girl, wearing little clothing walking into the night, two big men on either side.”

The girls in CERI’s support group for young women made paintings in response to a documentary about the commercial sexual exploitation of children.

As they went around the room sharing their paintings and poems, several girls described encounters they had had with underage prostitutes. “The movie made me think of all the things she wanted to be,” said one girl, recalling an old friend who dropped out of school after becoming involved with a pimp. “She said she wanted to be a veterinarian.”

The program coordinator for the group, who is 20, described discovering that one of her boyfriend’s friends was a pimp. “He showed up to our house with this girl, and when she wouldn’t tell him where she had been he beat her up,” she recounted.

Everyone in the room looked horrified. One of the mentors asked why she hadn’t called the police. The girl responded, “We live in Oakland. The police would have come an hour later and he [the pimp] would have been gone.”

Afary is saddened—but not surprised—by the familiarity the girls in her group have with the realities of prostitution. Afary started this general prevention and early intervention program when some of her adult clients asked her to help them prevent their children and grandchildren “from reaching their destiny,” as they put it. This perceived fate includes involvement with gangs, selling drugs, and living a life of crime.

Soon after she formed the group, Afary realized the extent to which commercial sexual exploitation or CSEC—a term experts use instead of “prostitution” because they believe that children do not voluntarily choose to work in the sex trade—was a problem for girls in Oakland, and saw a need to address it with her group’s girls. “I heard about it ten years ago, then I heard about it seven years ago, but it wasn’t until someone that I knew was involved that I think I really understood it,” she said.

Two years ago the daughter of one of Afary’s adult clients disappeared. The family suspected that she had become involved with prostitution and was being held by a pimp. Phone calls from the daughter to her parents confirmed this inkling, Afary said. “I heard her voicemails, asking—begging—for help,” said Afary. “It was only then that I realized how the danger was really threatening our young girls.”

Barbara Loza-Murieria, program specialist for Alameda County’s Interagency Children’s Policy Council in the Sexually Exploited Minors network, said that pimps who go after young girls do so in very intentional ways. “Pimps troll and hunt for children with vulnerabilities,” she said, “the child who is shy, or sad, or troubled. They are experts at it.” Loza-Murieria said that this often overlaps with children who are already runaways or at-risk. She says that a child out on the street alone for 72 hours will most likely be approached by someone who wants to exploit them.

Loza-Murieria described a clear five-step process that happens after this sort of initial encounter: “Recruitment, seduction, isolation, coercion, and violence. It’s similar to an abusive relationship.” She depicted an elaborate process in which pimps will first befriend a girl, then romance her, isolate her from family and friends, and eventually convince or force her to have sex with strangers. Pimps will often slowly reveal to girls the violence that exists in their worlds. “If someone is beating the crap out of someone, wouldn’t that be enough to send that child away?” Loza-Murieria asked rhetorically, but added that some girls might not react by fleeing. “To children coming from poverty, where there is already exposure to violence, there’s a scary aspect to it but there’s also an aspect of force and strength,” she said.

Joshi said that the majority of girls she sees who are involved with commercial sexual exploitation are African American, and added that the socioeconomic challenges in the African American community put these girls especially at risk. But, she said, “It’s important to not put a slant on race, but to think about all girls.”

Joshi did add that having parents who don’t speak English—well or at all—is a risk factor for girls. These parents aren’t able to monitor the online activity of their daughters, or understand phone messages that might indicate that their daughter is being solicited sexually or is involved with a pimp. “It’s just another barrier,” said Joshi.

One of Mona Afary’s main goals at CERI is facilitating healthy intergenerational communication within Cambodian refugee families, because she sees a big disconnect between parents and children. This is partly because there’s such a disparity in their life experiences, she said—the parents lived through war and genocide and their children, who were all born in the United States, did not. But there are also cultural differences, she said: Their children are American, they speak English fluently, they go to school here. They don’t always hold onto their parents’ Cambodian customs. Afary worries that these factors lead to a lack of understanding between parents and teenage children, increasing the vulnerability of young girls. Additionally, refugee parents who worry that something may be wrong don’t always know how to speak to American authorities.

Loza-Muriera says that Southeast Asian teens and their families generally have less interaction with public systems—like those that provide juvenile justice, welfare and mental health services—than other ethnic groups. “The concept of mental health is sort of unknown to their culture,” she said.

She noted another concern, specific to Cambodians. “They have experienced war and oppression, many do not trust the authorities,” she said. “By the same token they want help, but often have no understanding of the system of how things work. These are all barriers to their children.”

But Loza-Muriera said that the community does trust Mona Afary, and that to its members, CERI feels like a home, not a mental health facility. It occupies the second floor of a Victorian mansion, and seems more like a community center or private home. Only three rooms down from where the girls’ support group is held, older Cambodian women prepare food and pray in a spiritual space—a makeshift temple.

Though there is reason for Afary to be concerned about young people in the Cambodian community, Oakland has been in the spotlight for the sex trafficking of minors of all ethnic backgrounds for several years. “Oakland is unfortunately known as a hub for this, but is also known for being a leader in addressing it,” said Loza-Muriera.

“Ten years ago a lot of focus was on international trafficking” she said, but since then attention has shifted to local teens, as the OPD and advocacy groups became more aware that they were being exploited, too.

According to Sgt. Joshi, who has been working in OPD’s vice and child exploitation unit since its creation in 2000, the OPD was one of the first police departments that recognized girls involved with sex trafficking as victims, instead of perpetrators. Police officers discovered a growing number of minors involved in prostitution in the late 90’s, she said. “We would arrest prostitutes and then discover that they were juveniles,” Joshi said. Adult prostitutes also told officers about young girls who were involved with pimps. The OPD worked with investigators who were already trained to work with adult prostitutes and gave them additional training to focus on underage girls.

Still, there is a grey area in the system about what to do with girls who are arrested by police. When Joshi or other officers find victims on the street, it’s up to them to decide if it’s appropriate to take them back to their family members, to group homes, to Juvenile Hall, or to Alameda County’s Children’s Assessment Center, where police officers and Child Protective Services staffers determine where children, often removed from their homes, should go next.

Joshi said that locking girls up suggests that they are criminals, but that when an officer does this it is with the girl’s safety in mind—it prevents her from immediately returning to her pimp. “If a girl doesn’t identify as a victim, we can’t put her in a program that she could walk back out of, because she’ll just go back to the life,” Joshi said. For example, the Children’s Assessment Center doesn’t have lockdown capabilities, Joshi said, “So a girl could call her pimp and be out the back door in 20 minutes.”

Joshi added that girls sent to Juvenile Hall are separated from teens who have been arrested for other reasons and are placed in an area with other exploited minors.

Loza-Muriera agrees that there isn’t one all-encompassing solution about where to take arrested girls. “There’s no one stroke for every kid. Everyone’s different. If they could take a child to a safe and secure place where that child could be held they would. But no such place exists,” she said.

DreamCatcher Emergency Youth Shelter in Oakland, a center for homeless and runaway children aged 13-18, recently got funding to create a whole new floor dedicated to victims of commercial sexual exploitation—a solution Loza-Muriera said would fill this gap in social services. The shelter is meant to be a safe place for victims of commercial sexual exploitation to go, without locking them up or returning them to potentially unstable family situations. But so far, construction has only just begun.

In the meanwhile, those who work with young girls hope that making them aware of the dangers of prostitution, and being comfortable sharing their feelings and experiences about it, will prevent them from getting caught up in the life. At the movie night, Afary said she wasn’t worried about the girls being too young to deal with the topics addressed in the documentary, because she realizes that they must see things in their neighborhoods that she never does. “I get agonized when I see how they have become used to, are witness to so much aggression and brutality around them,” she said. “It’s sort of like living in a war zone. I never lived in the war zone, and I’m still not. I’m just visiting it.”

At the Oakland Museum, Question:Bridge facilitates a high-tech conversation among black men

Image courtesy of the Oakland Museum of California.

A single television screen flashing intermittent images of African-American men and boys—elementary school aged kids through senior citizens—welcomes visitors to the Question:Bridge exhibit at the Oakland Museum of California. One by one they look into the camera lens, silently meeting viewers’ gazes.

Five more screens line the wall just around the corner from the first TV, flashing more images of black men. Some have silver hair and wear coats and ties. Others are bald and have glasses. Some are dreadlocked, some are pierced, and several men wear the telltale bright orange of prison uniforms. As on the first TV screen, each man looks directly into the camera. But instead of silence, these men speak. As each one appears he either asks a question or responds to one asked by another man on a different screen, simulating an actual real-time conversation between hundreds of men.

One man asks, “For all the gay black men out there, how do you really feel about yourselves? What are you doing in order to survive?”

One man responds, “When I decided to love myself more than what other people felt about me, I felt free.”

Another says, “One of my tactics is cutting people off. People that I know and love like my own dad, in order to not feel angst and oppression.”

“Here you have the unrehearsed, totally spontaneous expression of truth—a concentrated exposure to the thinking of black men,” said photographer Chris Johnson, who is also a California College of the Arts (CCA) professor, longtime Oakland resident, and one of the four brains behind Question:Bridge.

The exhibit is the result of a four-year long project by Johnson, Hank Willis Thomas, Bayeté Ross Smith and Kamal Sinclair. The exhibit is debuting in four U.S. museums simultaneously: the Oakland Museum of California, the Brooklyn Museum, the Utah Museum of Contemporary Art and the City Gallery at Chastain in Atlanta, Georgia. The artists recently traveled to Park City, Utah where the Question:Bridge project was an official selection in the 2012 Sundance Film Festival.

The Question:Bridge team worked intensively over the past four years to create this project. But its roots extend even deeper than that, all the way to 1960’s Brooklyn, where Johnson spent his childhood. “I was 16 years old in 1964,” Johnson said. “That means I was old enough and conscious enough to see the impact of the civil rights legislation.” What he saw was a new class of black people. “There were lots of role models,” he said, “You didn’t have to go far for a black doctor.”

But Johnson also witnessed people who suddenly had the means to leave Bed-Stuy—his Brooklyn neighborhood—and did. He looks back on this time as the beginning of the fracturing of the black community, a theme he has explored in his work ever since.

In 1994 Johnson created The Roof is On Fire, a performance art piece, with fellow California College of the Arts professor Suzanne Lacy. They put 100 cars on a rooftop garage in Oakland and put 220 teenagers in those cars, instructing them to converse about set topics like sex and race, without getting specific. As the young people talked with their car windows rolled down and the convertible rooftops opened, onlookers walked around and listened to their unscripted, unedited conversations. The response to this deceptively simple project was overwhelmingly positive. It seemed to Johnson that people left thinking differently about young people. “It made me realize you could come up with ways of communicating information that could really effect change,” Johnson said.

In 1996 Johnson created what became the prototype for Question:Bridge, a video installation called Re:Public. It was at this point that Johnson revisited his early experience of seeing wealthier blacks leave Bed-Stuy. “The fact that the black community is so radically divided at this point is something that really speaks to me,” he said.

As a fine arts photographer with no previous video experience, Johnson thought the Re:Public final product was “crude” and tucked it away without taking it any further. He did, however, give a copy to his friend Deb Willis, the chief photography curator at the Smithsonian, who tucked it away herself. In 2002 Deb Willis’s son, Hank Willis Thomas and his friend Bayaté Ross Smith went to California College of the Arts to earn their MFAs, where they studied with Johnson. But it wasn’t until a few years after they graduated and were establishing themselves as artists that Thomas found his mother’s original Re:Public video. Thomas had just received a grant, and was exploring similar themes of race and identity in his work. In 2007, he decided to try to convince Johnson to re-do the original project with more time, energy and resources.

Johnson agreed and he, Thomas and Smith set to work; Sinclair joined in later. The premise was pretty simple: They decided to travel throughout the United States and get black men to ask and answer questions on camera wherever they went. Johnson recalls saying to the men he met, “So, as a black man, I’m sure there are questions that you would want to ask a black man that you feel different from.” He would then instruct them to “look into the lens, like you’re asking that person.” He would have each man ask questions, and then answer a question that another man had asked.

“We were just two artists doing this kind of unusual project” Johnson said, “so we had no access to famous guys, celebrities. So we just started with regular black guys.”

Their first stop was Birmingham, Alabama because Thomas had a speaking engagement that funded the trip. Johnson was sitting next to a black man on the plane on the way there, so he decided to ask him to participate in the project. The man said yes, and promised that he would bring three of his friends to the artists’ motel room. They often met the remaining hundreds of participants by similar random means. In Chicago, Johnson asked a black museum guard to participate. He noticed a man dressed in the red beret of a Guardian Angel (an international organization of unarmed, civilian crime patrollers) outside and brought him into the fold as well.

Over the course of four years, eleven cities and one jail, the artists rarely had anyone turn them down. “Every black man would immediately understand what we were doing,” Johnson said. “They were able to give such spontaneous answers because they’ve been thinking about these questions. They live under this question cloud. All we’ve done is tapped into this question cloud.”

When the televisions play in the museum exhibit gives the impression of a round-table discussion, but most of these men have never met one another. Meeting is not the objective. “The real point of the project is for them to ask questions that are so essential, and to feel safe enough with the process to do that,” Johnson said. “Their truths are meeting through the project.”

Listeners may feel like the viewers of The Roof is on Fire did—like they’re eavesdropping on usually-unheard conversations. Only in Question:Bridge it also seems like the audience is listening to conversations that don’t normally happen.

Question:Bridge has been successful as an art exhibit, but the team of artists is also passionate about a curriculum they have developed for high schools throughout the country. Though the project is focused on African-American men, the curriculum explores identity issues in general. It asks students to examine the complex relationship of race and socio-economic issues in any demographic. Students watch films and look critically at artwork, but they also interview people in their own communities and produce visual, analytical representations of them.

Oakland Unified School District is piloting the curriculum in McClymond’s High School. Districts in Hayward and Brooklyn, New York are also going to use it. Though McClymond High School is using the curriculum specifically with African-American male students in their Manhood Development Program, Hayward’s district is interested in adapting it for students of all races, genders and backgrounds. Chris Johnson is eager to see both results. The Question:Bridge team doesn’t intend for the curriculum to be race-specific. “We started with black men because we are black men and we’re artists,” says Johnson, “but we hope other demographics will use the methodology themselves.”

Students at Oakland International High School describe their immigration experiences with graphic art

The giant, golden arches of the McDonald’s tower over the field behind Oakland International High School (OHIS) in Temescal. Clanking, whizzing sounds of passing BART trains—traveling on the elevated leg between the MacArthur and Ashby stops—echo through the air. But even though it’s a stone’s throw from the busy streets of the city, OIHS feels far away from everything, like a quiet sanctuary for its 300 students.

OIHS’s art classroom lies in one corner of the school’s courtyard, where colorful murals, plants and flowers encircle benches made from planks of wood perched on tree trunks.

OIHS’s art teacher, Thi Bui, starts asking her students questions before they step inside her classroom. “What is art?” reads one sign taped to the outside of her door. Another one, posted below the first, says, “What can drawings communicate?” And a third asks, “What can comics communicate?” Bui wants her students, all recent immigrants and many still struggling to learn English, to contemplate about big ideas.

Bui has just begun her fifth year teaching at OHIS. During her time here she has worn several hats. She taught social studies for one year, then art, reading and literacy for another; for the past two years she’s been the art and media teacher. As she begins her third year teaching a combined comic book and oral history curriculum, she finds she is doing a little bit of everything.

Each fall, Bui asks her ninth and tenth graders to tell their immigration stories in comic book form. Her students published their first collection of comics two years ago, and called it Immigration Stories. Some people would call these books “graphic novels,” but Bui prefers the word “comics,” even though they’re rarely funny. The graphic narrative Maus, by Art Spiegelman, about his father’s experience during the Holocaust, made this style of serious comic book famous. It won the Pulitzer Prize in 1992 and has been called a comic book, graphic narrative and graphic novel interchangeably. “Comics are a medium, not a genre,” Bui says, “It’s just sequential storytelling with words and pictures.”

The transition from teaching social studies to art came naturally to Bui, who has degrees in both subjects. “I had a dream of teaching history backwards, to start with current events and piece it together to see how it got that way,” she says. “Kids need things contextualized.” Bui wants her students to understand history as ongoing, something they play a part in. Her goal for the oral history component of the comic book project is to help her students see that “their stories are a part of something bigger,” she says.

An immigrant herself, Bui came to the United States as a three year-old in 1978. She is now well-versed in her parents’ immigration story from the 1970s, having researched their experience extensively to write and draw the first two chapters of what she plans to be a 15-chapter comic book about her family’s life in Vietnam and immigration to the United States, called The Best We Could Do.

Bui has thought a lot about how immigration to the United States has changed over time, and continues to transform. “I tell kids that every generation of immigrants looks different. Some came on ships and saw the Statue of Liberty,” she says. “Now some walk through the desert or come on refugee airplanes.”

Bui’s classroom reflects this constant shift. On the white board, underneath the day’s homework assignment, are pieces of cardboard cut into the shape of comic books’ recognizable speech bubbles, thought balloons and narrative boxes. Three tell a hypothetical story: “We walked for 4 days in the desert,” reads a narrative box. “Can I have some water Papi?” asks a speech bubble. “So thirsty! But there’s only enough for one person,” says the thought balloon.

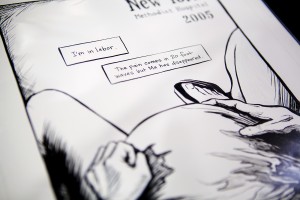

By asking her students to create these comics, Bui is not only teaching them to tell stories through art, but she is helping them make sense of their lives and process what they have gone through. Bui has only reflected on her and her family’s immigration experience as an adult. In fact, she says that creating her first book helped her become an adult, even though she was already a grown woman, and a mother, when she wrote it. The first chapter of her book, titled Labor, provides a detailed account of the birth of her son. Page one features a precise drawing—an aerial view of Bui’s very pregnant belly. The chapter illustrates her difficult labor, weaving in stories about the complicated pregnancies Bui’s mother went through both in Vietnam and en route to the United States. Bui says that having a son made her feel closer to her own parents, realizing how hard it must have been for them to move to a new country with three small children.

One of the themes Bui concentrates on is the disconnection that forms between generations of immigrant families. Immigrant children will often acclimate quickly to their new cultures, while their parents might adjust more slowly or not at all. Bui tells this story of a student’s mother: grappling with her 15-year-old daughter’s fast-paced relationship with a boyfriend, the mother asked Bui for advice. Bui responded by saying that “they should just talk to each other,”—often easier said than done. New immigrant families often learn languages at different paces. Parents sometimes hold on to customs and memories from their home countries, something hard for children to do, especially when they immigrate at very young ages.

Bui knows how difficult it can be. When she was a teenager in Southern California, Bui’s parents were afraid they would lose control of her and her sisters. “They were very strict. They came to the United States and watched Fast Times at Ridgemont High, then they didn’t want to let us out of the house,” Bui says. Bui’s father, a well-read poet, was never fluent enough in English to have the kinds of detailed intellectual conversations she craved. “I can’t access that part of him,” she says.

Another recurring thought Bui has relates to “the effects of war on ordinary people.” She sees it in her parents, in the neurosis her dad still carries with him after witnessing the Vietnam war. She sees it in her students, as well, especially when she reads their comics. “Sometimes the stories are so intense I start crying,” she says.

Bui worries that depression is a serious problem for OIHS students. Some of them have been through horrific things in their home countries, and then struggle to transition into a brand new culture with strange faces, languages and customs. Her students have experienced a lot in their short lives. At times, it is readily apparent, like when a tall boy with a scarred face walks through the school courtyard. Other times it is only when students speak about their experiences traveling to the United States on UN airplanes that it becomes clear this school is unique. One ninth grader, Madhavi Dahal, talks about how her family escaped from Bhutan as she prepares to draw a thumbnail sketch for her comic book. “The king tried to kill them and they ran away,” she says, describing how her parents were forced out of Bhutan for being in the minority of Bhutanese people who spoke Nepali. Madhavi is using her comic book to tell her immigration story in four parts: “In Bhutan, Nepal, airplane, then here.”

Elvis Nguyen, a 12th grader who recently adopted this new, American-sounding name to replace Qua, his Vietnamese one, was nervous about putting his life out on a page when he made his comic book with Bui two years ago. His story told of the challenges he faced when he came to the United States six years ago. Elvis had never drawn before he made his book. He worried about putting his feelings into images that people would be able to see. “I don’t want to share my feeling, and share it in a book,” he said. “I’d rather keep it to myself.” But he went ahead and did share his private feelings and experiences—one page shows his father sitting at a desk, frowning, struggling to pay bills. Making the comic turned out to be a positive experience for him. It forced him to talk about how he felt with his parents. When Elvis showed them his book, translating it into Vietnamese for them, he wasn’t nervous anymore. “It’s like all the things I want to say is here,” he says, pointing to his comic. His parents loved it.

Bui is amazed at how much she has learned about her students through this project. Two brothers, Clay Mu and Eh Mu, lived in a refugee camp in Thailand before they came to Oakland by way of Los Angeles and Tokyo. They both took to drawing immediately, even though it was brand new to them. Bui’s face lights up when she describes their talent, how they can recreate, from memory, the refugee camps they lived in on paper.

“They have an image of their refugee camp imprinted on their retina,” she says. Bui has learned a lot about her students through this comic book process, more than she would have in any other class. Though she didn’t start out with that intention, it has brought her closer to her students and, she hopes, has helped them acclimate to their new lives. Bui likens the process of her visual storytelling curriculum to counseling. “A lot of what therapy does is help you create a meaningful narrative out of events that have troubled you for a long time. If that’s not comics, I don’t know what is,” she says.